Occurrence

Both creeping and spear thistle are widely distributed throughout the UK. The main thistle species growing in both arable and grassland situations is creeping thistle. Spear thistle, the commonest thistle in the UK, and other less common thistle species, occur mainly as weeds of grassland. Three sow-thistle species all occur in arable situations, with smooth sow-thistle being the species most frequently encountered. All three species are widely distributed in England and Wales but have a slightly more restricted distribution in Scotland.

Thistles remain a significant problem in some perennial crops and also in permanent pasture. Sow-thistles tend to be a greater problem in non-cereal arable crops.

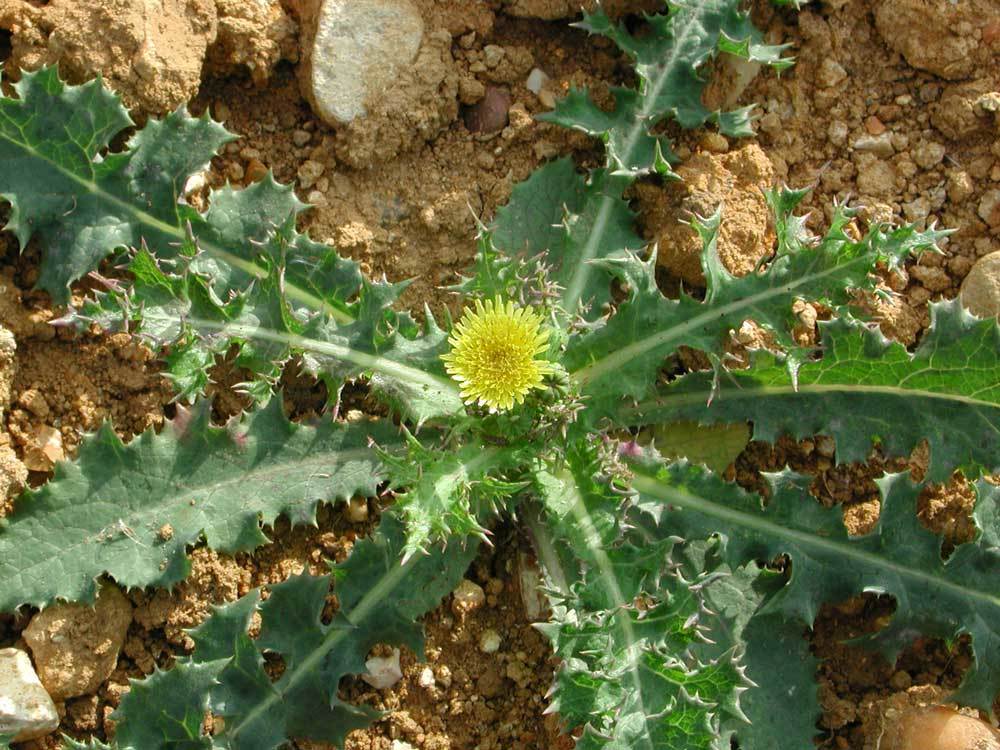

Identification

Creeping thistle is a perennial with extensive creeping underground roots whereas spear thistle is a biennial with a very deep tap root. Young plants of these two species can be difficult to tell apart, but creeping thistle has hairless upper leaf surfaces and spineless stems whereas spear thistle has rigid bristles on upper leaf surfaces and a stem with discontinuous spiny wings. Leaves of both species are distinctly spiny. Both produce purple flowers but these tend to be in clusters of 2 – 6 in creeping thistle but solitary, or in small cluster of up to 3, in spear thistle.

Smooth sow-thistle is an annual with softly spiny leaves clasping the stem with pointed auricles (= small ear-like projections from the base of the leaf). Prickly sow-thistle is also an annual, looks similar, but has glossy leaves with sharper spines and rounded auricles where the leaf meets the stem. In contrast, perennial sow-thistle has spreading, creeping underground roots, softly spiny leaves with rounded auricles. All three species have yellow flowers with a diameter of 20 – 25 mm in smooth and prickly sow-thistle, but 40 – 50 mm in perennial sow-thistle.

Agro-ecology

Creeping thistle is a tall, competitive plant which owes its success to the presence of an extensive system of underground roots (often incorrectly called rhizomes) which can extend well below tillage depth, although most roots are in the surface 30 cm. Root fragments, which commonly result from cultivations, can readily regrow to produce new plants but may also remain dormant in the soil for a considerable time if undisturbed – for many years, it is claimed. Each year, the foliage dies back in late autumn and regrowth reappears in spring. There appear to be widely differing views on the importance of seed production in the spread of creeping thistle. Individual plants bear only male of female flowers (dioecious) from July onwards, plants are insect pollinated and male and female plants need to be within about 30 m of each other for high levels of cross-pollination to occur. The feathery pappus attached to the seed would appear to assist in its dispersal but much of abundant ‘thistle down’ contains relatively few fertile seeds and these tend to be deposited within a short (< 25 m) distance of the mother plants. Most seeds are retained in the heads and are not shed until these drop to the ground very close to the mother plant. Seed production is highly variable and viability is often low, probably due to inefficient pollination. Average seed production in an arable crop situation is typically about 1000 seed per plant. Seeds tend not be highly persistent in cultivated soil and the seedbank may be low even where dense patches of thistle occur. However, some seeds may persist for over 5 years, especially if undisturbed. Seeds mainly germinate in April or May. Overall, it appears that localised spread within or between fields is largely by vegetative means, due to lateral growth or movement of root fragments, rather than by seed movement. However, spread by seed may be more important than generally assumed as thistles soon appeared on set-aside land, even where previously absent.

In contrast, spear thistle and smooth and prickly sow-thistle are spread only by seeds with seedlings emerging in both autumn and spring. Seedlings are largely derived from seeds within 3 cm of the soil surface. The seeds are not highly persistent in the soil, but some may survive several years especially in undisturbed soil. Seeds of all three species are dispersed by wind, although mainly over a relatively short distance (< 10 m) from the mother plant. Perennial sow-thistle spreads by underground roots but, in contrast to creeping thistle, these are largely confined to the surface 15 cm. Spread by seed is also important and these are dispersed by wind. Seeds may survive up to 5 years in soil and seedling emergence is largely confined to the spring.

Damage

Most information is available for creeping thistle. Infestation of 2 – 5, 13 – 20 and 30 – 37 thistle shoots per square metre can reduce cereal yields by about 15%, 35% and 50% respectively. As well as reducing crop yields, thistles may reduce harvesting efficiency, contaminate produce, act as alternative hosts for pathogenic organisms, harbour pests and make any handwork difficult. In pastures and meadows, thistles reduce grazing utilization, cause ulceration of sheep’s mouths and spread of the disease orf and reduce the quality of hay and silage. Creeping and spear thistle are two of the five weeds classified as injurious under the Weeds Act 1959, the others being broad-leaved dock, curled dock and common ragwort.

Management information

See other information sheet (Broad-leaved weeds: occurrence, agro-ecology and management) for best approaches to integrated weed management of broad-leaved weeds.

- The traditional method of controlling thistles, non-chemically, was to destroy the top growth and starve out the roots. This is still the primary aim today.

- Creeping thistle infestations tend to occur in discrete patches in many annual and perennial crops as well as in grassland. Map and record where these occur, and target control measures within, and around, these patches with the aim of minimising further spread.

- Repeated, intensive cultivations can fragment the roots of creeping thistle and perennial sow-thistle and gradually reduce infestations over a period of years by exhausting food reserves and exposing the roots to frost or desiccating conditions. Operations should be timed to destroy creeping thistle shoots as they approach 7.5 cm tall. Total eradication by cultivations alone is unlikely. Occasional cultivations are likely to make the problem worse by forming numerous root fragments which are likely to increase the number and spread of plants in the field, thus extending the affected area.

- Really deep ploughing can be effective against creeping thistle and perennial sow-thistle but is best used in combination with other control measures.

- Rotations which include spring as well as autumn sown crops may allow more control opportunities. Thorough winter cultivation followed by an inter-row cultivated crop or a competitive smothering crop, such as arable silage, can greatly reduce infestations of creeping thistle and perennial sow-thistle but will seldom eradicate them. Rotations may also enable the use of a wider range of herbicides against all thistle species.

- The only moderate seed persistence in the seedbank of all thistle species means that populations, at least of annual species, can be reduced over a period of years if seed production is prevented. Consequently, preventing seed production is an important goal in long-term weed management of all thistle species.

- Cultivations will encourage some seeds to germinate, but some will remain dormant, especially if deeply buried. Establishing spring crops by direct drilling or with minimal soil disturbance should reduce the numbers of thistle seedlings emerging in the crop.

- Thistle seedlings are susceptible to competition, especially at the early growth stages, and a strongly competitive crop will assist other control measures.

- Hoeing in row crops and harrowing can be effective in controlling many broad-leaved weeds, especially if carried out while weeds are small.

- Prevent importation and spread of root fragment and seeds. Root fragments may get moved on cultivation equipment and seeds in contaminated crop seed, hay, straw, manure and irrigation water.

- Spear thistle does not usually persist in arable rotations or routinely cultivated soils, but is encouraged by fallows, grass breaks and perennial crops. In contrast, the sow-thistle species are intolerant of grazing so do not persist in grassland but are more commonly encountered as arable weeds.

- Heavy infestations of creeping thistle in grassland is an indication of unbalanced grazing pressure, involving under-utilisation of the herbage during the growing period of the thistles combined with over-grazing during the winter and early spring. The resulting sward tends to become open and start growth late, offering little competition to the emerging thistle shoots which then tend to be avoided by grazing stock. This situation is common on sheep farms. Close stocking, preferably with cattle, or cutting for conservation at a young stage, combined with at least moderate fertiliser use, can reduce infestations progressively.

- Cutting, mowing or grazing thistles in grassland can progressively weaken plants, but cutting needs to be done as low as possible to remove all the leaves. The most effective timing is at the early flower bud stage. It must be repeated at least twice during the growing season for several years to have a permanent effect. Pulling up plants is more effective than cutting.

- In grassland, minimising sward damage from trampling, poaching and uneven slurry application will prevent thistle seedlings establishing in the disturbed patches.

- Control of thistles is largely dependent on herbicides on most farms, so maintaining the availability and efficacy of a wide range of herbicides is essential.

Herbicides and resistance

- Chemical control of creeping thistle should be part of an integrated management approach which include, where feasible, cultivations, mowing or grazing, and competitive crops. Creeping thistles generally have a varied response to herbicide treatment, as there is much variation within the species including the rooting system and growth habit.

- Clopyralid is the most effective selective herbicide available for controlling thistles and is approved for controlling creeping thistle and smooth sow-thistle in a wide range of arable and perennial crops and also in grassland. It also controls mayweeds, but otherwise has a narrow weed control spectrum, so is often used in mixture with other herbicides to broaden the range of weeds controlled. Herbicide application should occur when creeping thistle plants are actively growing, ideally in April or May, but recommendations vary with the specific crop. Efficacy will be reduced if cultivations are carried out soon after spraying.

- Clopyralid has been detected in water at levels that regularly exceed the EU Drinking Water Directive limit for individual active ingredients (0.1μg/L). This puts the UK at risk of non-compliance with Water Framework Directive objectives for drinking water catchments. Appropriate measures should be taken to minimise the risk of clopyralid leaching to water.

- Synthetic auxin herbicides, such 2,4-D and MCPA, are also effective at controlling thistles and are best applied in May/June if conditions and crop permit. Although control of leaves and shoots is usually good, translocation of the herbicides to the roots of creeping thistle is less effective than with clopyralid, so overall control tends to be less effective and greater regrowth is likely after synthetic auxin treatment.

- MCPB can be used for control of thistles in peas.

- Sulphonylurea herbicides, such as metsulfuron+thifensulfuron can be used to control creeping thistle in cereals and prosulfuron controls sow-thistles in maize.

- Glyphosate can be used to control thistles non-selectively but will kill or severely damage other plants exposed to the spray. Best applied between June-October, when thistles have 30-60cm of growth, reached the flowering stage but before they die back.

- Several cases of evolved herbicide resistance have been reported in different thistle species in other countries, but not so far in the UK. In creeping thistle, resistance to synthetic auxin herbicides has been reported in Hungary and Sweden. In smooth sow-thistle, resistance to synthetic auxins, sulfonylureas and glyphosate has been reported in Australia. In prickly sow-thistle, resistance to sulfonylureas has been reported in Canada, France and Norway.

- None of the reported cases of resistant thistles involve clopyralid, but resistance to this herbicide has been reported in three other weed species, in New Zealand and Canada.

- Other herbicides that give some control of thistles include s-metolachlor (maize), napropamide (various crops), dimethamid-p + quinmerac (winter oilseed rape), prosulfocarb, pendimethalin and diflufenican, although several of these have only ‘off label’ approval in minor crops.

- Spot spraying using a knapsack sprayer is an effective method of applying herbicides to patches of thistles.

- Thistles represent a relatively low resistance risk compared with many other grass and broad-leaved weeds. However, the cases documented here show that the risk resistance needs to be taken seriously. If resistance is suspected, collect a seed sample and have it tested.